Last week, a jury of his peers found former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin guilty of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter. That’s legalese for saying that Chauvin will face actual consequences for kneeling on George Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes - 9:29, according to the most precise reckoning from body camera footage - while the stricken man begged for help. Floyd actually spent more than half that time flailing in the midst of a series of seizures, and then was completely unresponsive, all while bystanders pleaded with Chauvin to show a modicum of humanity.

Given the straightforward illegality and brutality of Chauvin’s actions, and the fact that several bystanders immediately recorded and uploaded videos of the incident, it shouldn’t be surprising that he was found guilty. Yet Chauvin’s conviction is the exception, rather than the rule. The former police officer acted as he did last May because of the ironclad certainty that he wouldn’t face any consequences for his actions, no matter how egregious.

Thirty-two bullets fired into Breonna Taylor’s apartment, an arm across Eric Garner’s neck, the knee pinning George Floyd to the ground: this is American policing laid bare, reduced to its most fundamental drive, its perpetrators effectively guaranteed that their actions will be met at least with an absence of disapproval, if not an outright blessing. How many times in the past several years have we seen law enforcement officers walk away from incidents no less clear in their obvious wrongness?

Chauvin had every reason to think that murdering George Floyd was part of the job.

American policing, in its current form, is dedicated to the defensce of a particular social order rooted in both race and the defense of property. The social order is only tangentially connected to the law; the law is a tool for enforcing it, but the identity of the person who commits a crime determines the punishment and response, not the crime itself. This is a hierarchical conception of the world, divided between those who deserve protection and those who must be kept in their place. The police, then, are the thin blue line standing between those two groups, the keepers of the social order.

The responses to the verdict from the hard right - which we might characterize as anti-anti-Chauvin rather than pro-kneeling-on-an-unresponsive-man’s-neck - and current defenses of policing more generally are all implicit or explicit defenses of this social order. If you like the way things are, then brutal police actions have to be not just condoned but actively promoted. Attempting to reform or abolish policing is less about the obvious wrongness of their actions than a referendum on the broader American order they represent and enforce.

That, not whether uniformed thugs like Derek Chauvin (with long histories of prior abuse) should be murdering people on the street, is the basis of the argument. Unless and until the concept of the social order that policing reinforces changes, with its hierarchies of in- and out-groups, then policing will remain essentially as it is. The Derek Chauvins of the world will remain in place, protected by their peers, as they club and kneel and shoot with every expectation of impunity.

On an entirely different note, we have a collaborative roundtable coming this week on Discontents: a discussion of Nu metal, how and why it’s been forgotten, and most importantly, whether or not it’s actually as terrible as we’ve been all been told since the heyday of Limp Bizkit and Korn.

Before we turn things over to the rest of the Discontents team, can I ask you to do something? If you’re not already signed up to our email list, please do. It’s absolutely free and you’ll be sure never to miss an issue:

If you are already a subscriber, please help us spread the word about Discontents by sharing this and our other posts on social media! Our hope is to keep growing this project, but we can’t do that without your support. Thanks for reading!

Welcome to Hell World

Luke O’Neil

Two weeks ago today Josh Albert was set to take off on a trip to South America. He was walking out of a FedEx in New York City after getting his passport and vaccination papers in order when the right side of his body stopped working. “My speech was messed up. I made it about a half a block and I had to sit down,” he said. “I really didn’t know what was going on. I thought, oh, this will pass.”

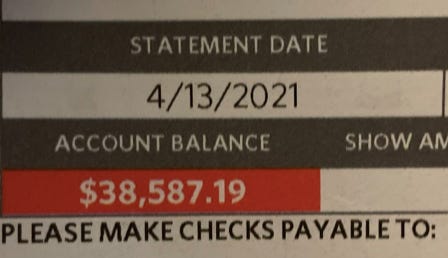

Having no health insurance, and so naturally afraid to go to the hospital, he tried to walk it off. An hour or two later he was rushing to the nearest emergency room, in an Uber of course, still at this point wary of potential bills. He’d end up getting those anyway.

I spoke with Albert about his experience having an unexpected health emergency then being pummeled with bills before he even ever got to fully understand what had happened. Subscribers can read that piece here.

Today I also have a piece written by Zaron Burnett III. It’s about Black cowboys and cultural mythology and what we remember about ourselves. Burnett previously wrote for Hell World on what it felt like as a Black man to wear a mask in the airport in the early days of Covid.

I’m lucky that my Pop’s memory stretches back to a time when he regularly saw Black men with horses each morning. Not cowboys, per se, milkmen. But it made it much easier for him to imagine Black cowboys. Much easier than it was for me.

Wars of Future Past

Kelsey D. Atherton

What is the correct way to mine a high-profile death for engagement? Last week saw a lot of grim necromancy. After the verdict in the Chauvin trial, Pelosi assigned deliberate political martyrdom to George Floyd for simply trying to live his life. The Bleacher Report, meanwhile, trotted out the death in uniform Pat Tillman, the former Arizona Cardinals safety who left the NFL to enlist, became a ranger, and was then shot by his own men while on patrol in Afghanistan. That last part was missing from the tribute; if the goal is adoring retweets about a football soldier hero, much harder to get them with complexity.

In this weeks’ upcoming Wars of Future Past, I dive into the way Tillman’s enlistment and death became a driving narrative about the war. The cover-up of his death by American bullets, the orchestrated ceremonial martyrdom around an imagined battle that never took place, and the revival of Tillman as a totem of anti-war symbolism are all part of the same long legacy of forcing meaning onto a conflict whose defining trait is mistakes followed by tragedy.

With Biden’s recent announcement that the US ground war in Afghanistan will end by the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, grafted meaning is the only meaning left to extract from two decades of sunk costs and lost lives.

Foreign Exchanges

Derek Davison

Last week, Foreign Exchanges marked Biden’s Afghanistan announcement with a supersized podcast. Mena Ayazi, of Search for Common Ground, and (FX contributor) Kate Kizer, of Win Without War, joined me to talk about the withdrawal and how the United States might provide actual assistance to the Afghan people in lieu of endless war. Then I welcomed Fatemeh Aman of the Middle East Institute to talk about the effect the withdrawal is likely to have in Afghanistan and what role regional powers—China, India, Iran, Pakistan, and Russia—could play in helping to stabilize the country.

The Flashpoint

Eoin Higgins

My reporting on how Boston police handled the fall out from revelations of officer abuse and misconduct during anti-racism protests last summer continues. I profiled Jasmine Huff, a social worker who was attacked and trampled by riot police during a demonstration on May 31, 2020.

On June 5, Huff reached out to the police. A phone conversation was scheduled between Huff and two investigating officers, Sgt. Detective Philip Morgan and Sgt. Detective Michael Hanson, for June 23.

During the chat, Morgan and Hanson appeared uninterested in Huff’s account of her mistreatment and more invested in finding out what illegal activities she and other protesters did while protesting.

“I didn’t feel like I was treated with the empathy or concern that was warranted in that situation,” Huff said. “The focus was on everything but the topic at hand.”

The Insurgents

Jordan Uhl & Rob Rousseau

Our episode for this week is still in production, but if you haven’t yet, make sure you subscribe so you’ll be notified as soon as it drops. You can also get access to our premium episode from last week about the US Afghanistan “withdrawal” with Sarah Sahim and Arash Azizzada.

If you’re interested in what we’ve been up to individually this week, Rob has a new podcast episode out with Jesse Hawken & John Semley about the disaster that is unfolding in Ontario, Canada right now and how the incompetence and corruption of Doug Ford is directly responsible for it. Jordan has been helping raise funds for Yemen (you can still donate here if you are able) and as usual will be on TYT’s Deep Dive Tuesday at 2:30 est with Iman Saleh, general coordinator of the Yemeni Liberation Movement.

Discourse Blog

Hi everyone, Crosbie again from Discourse Blog. This week we continued our Worst Politicians in America series, following up on the list of the biggest scumbags in Texas with, well, the biggest scumbags in Wisconsin.

Much of our coverage still followed the Chauvin verdict, including my piece on the GOP’s crusade to crack down on legal protest and Rafi’s report from Minneapolis itself. Meanwhile, Jack blogged about Stephen Breyer’s RBG situation, I covered the Insider and Times Tech union drives, and Paul wrote about Republicans pushing to get an extremely pro-oil Democrat elected in Louisiana (they succeeded over the weekend).

We’ve also got Sam blogging about being owned into dust by Netflix’s The Circle, and Caitlin chased the rabbit through Nextdoor’s dad joke and racism cesspool. We’ll see you next week!

BORDER/LINES

Gaby Del Valle & Felipe De La Hoz

We’ve often said that immigration is a bizarre political issue that commands an outsize emotional response from a general public that, by and large, understands very little about how the system actually works. Last week, we explored a case in point: the asylum and refugee processes, which, despite the prominence of humanitarian migration in the national political conversation over the last several years, remain little more than abstractions to most people and are often conflated. Fear that the arrival of refugees would complicate the narrative of border crisis appears to be the primary reason that Biden, over two months after signing an executive order to overhaul the refugee admissions system, has not signed off on any increase to the numbers.

Two Fridays ago, he issued a memo seeming to formalize keeping the cap for the 2021 fiscal year at the current lowest-ever level of 15,000 (or equivalent to about 0.005 percent of the U.S. population). After swift public backlash, including from Congressional Democrats, the White House walked that back, claiming it had always been their intention to issue a revised number, to come on May 15. Still, it appears that the administration wants to jettison its early refugee ambitions, citing the partial collapse of both the government and nonprofit infrastructures that support the vetting, admissions, and resettlement of refugees from around the world. This argument is puzzling in that the lower refugee admissions are themselves often the cause of these processing problems: fewer refugees meant fewer need for staff and offices to handle them.

So far, the president’s rather tentative immigration strategy has seemed designed to appease conservative critics who will claim that he’s pro-open borders, but the broad condemnation of the refugee announcement proved that there are still a lot of progressives and even liberals out there who were fired up by immigration injustices during the Trump era and aren’t so keen on letting Biden get away with broken promises.

Perspectives: Past, Present, and Future

Patrick Wyman

Did you know that agriculture was independently invented in the remote, forbidding Highlands of New Guinea around 10,000 years ago? Neither did I, until a couple of months ago, and it blew my mind. Bananas, taro, and yams were all domesticated and cultivated there, creating an agricultural system that has lasted up until the present day.

This week on Perspectives, I’ll be digging into ancient South Asia and its first farmers, the antecedents of billions of people alive today.