The Global Policeman Turns Off His Body Camera

There are not two United Stateses of America. What America does abroad and what America does at home is one thing

When a U.S. special operations targeting unit known as Talon Alpha prepared to kill people in Syria who likely were not fighters for the so-called Islamic State, a curious gap in video footage would appear. According to suspicious military and intelligence officials who told The New York Times about Talon Alpha, the screens of drone operators wouldn’t display images of the strike site. One Air Force officer who “reviewed dozens of task force strikes where civilians were reportedly killed” told the paper that he “frequently” saw “cameras jerk away at key moments, as if they were hit by a wind gust.” The officer became convinced it was purposeful “only after seeing the pattern over and over.”

I’ve crouched in the claustrophobia-inducing refrigerated connexes that house drone operators, where the glow of the dual screens – one for an Army warrant officer, the other for a much-older contractor – were the only source of light. I’ve watched motorcycles and cars flit through the infamous “soda straw,” the stare of a drone camera that has no peripheral vision, and held my breath as the operators’ joysticks fixed the stare on one or another vehicle. The apparatus of secrecy concealing the realities of U.S. warfare in the 21st century ensures that not many people have seen that. Many more of us have seen or read about instances when police turn off their body cameras before or immediately after taking someone’s life.

Those of us who report either about the drone strikes or about the police slayings tend to write about these things as disconnected phenomena. They are in fact the same thing. Turning off the drone cameras is the same sort of cover-up for the military (and the CIA) that turning off the body cameras is for the police. There is not one United States that slays Black and brown people at home and a different United States that slays Black and brown people abroad. There is only one United States of America. Its works at home forecast its works abroad and its works abroad are beta tests for its works at home. A global policeman wants what his local counterparts want: qualified immunity.

Fred Ikle once wrote that all wars must end. That was naive and outdated when Ikle wrote it. The American way of war is global policing. Long before the U.S. occupied Afghanistan for 20 years, it occupied Haiti for 19, for the benefit of what today is CitiBank. Twenty-six out of 30 generals who conducted that counterinsurgency in the Philippines, according to Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous People’s History of The United States, were experienced in the final wars of extermination against the native nations of the west from the Civil War to Wounded Knee. Before it was called global policing, it was called manifest destiny.

Ours are not wars whose operations move toward conclusion. They are wars that subjugate populations, and subjugation requires persistence. Policing and warfare, in the context of global domination, are difficult to distinguish, because there isn’t a meaningful distinction. Talon Alpha is as American as apple pie.

In my newsletter FOREVER WARS last week, I mentioned last week that one of the legacies of the ongoing War on Terror is it that it provided the U.S. military with its first enduring footprint on the African continent. The commanding general of the U.S. Africa Command is Stephen Townsend. Before Townsend commanded AFRICOM, he commanded the U.S. war against ISIS during its most intense period, the 2016-2017 period when it waged months-long campaigns to retake Mosul and Raqqa. Before it was controversial, Townsend in 2017 boasted to Time that in a “dynamic strike” the decision to launch a missile occurs in “minutes.”

We now know the role of Talon Alpha in the process. When the Times caught up with Townsend, he was “dismissive of widespread reports from news media and human rights organizations describing the mounting toll” of dead civilians due to processes he, like his predecessors and successors, oversaw. The point of diverting the drone cameras is to make sure no one can prove Townsend wrong.

But, of course, even when everyone can see a drone strike incinerating innocent people, the Pentagon will hold no one accountable.

The AFRICOM job is Townsend’s reward for his command in Iraq and Syria. There is no reason to believe that, given the opportunity, he and the machinery he commands, which his successors will also command, will operate any differently. The ongoing War on Terror provides all the opportunity necessary, especially as it merges with a Cold War against China that considers Africa a field of imperial resource competition.

Remember that when you purchase a year’s worth of FOREVER WARS, you’ll get six free months at the paid tier of Luke’s WELCOME TO HELL WORLD and Derek’s FOREIGN EXCHANGES. Now for the rest of the Discontents crew.

Wars of Future Past

Kelsey D. Atherton

In November, the University of Arizona History Department announced a partnership with Age of Empires, to create an educational supplement within the game that could, after a quiz and some paperwork, count as a single credit hour towards a degree. It is, I think, a neat way to pull prospective students into a history department, but I couldn’t help feeling frustrated with the specific game as a tool of history.

In this week’s upcoming Wars of Future Past, I do a deep look at the specific limitations of Age of Empires for reflecting the big changes in early modern state formation and power. (Consider the new newsletter a spiritual sequel to this one). Age of Empires is a fine enough tool for learning about battles but a pretty weird one for understanding the progression of societies and organized violence over time, to say nothing of how it handles technology.

The Insurgents

Jordan Uhl & Rob Rousseau

This week we managed to take a little break from our normal depressing chit chat about living in and around a moribund, collapsing empire and just mainly talked about gaming. Congrats to Jordan who has been waging a subtle war of attrition over the last two years to ensure that the podcast would eventually just be a gamer’s rights thing. We’re joined by Trevor Strunk, PhD, aka Hegelbon, host of the No Cartridge podcast and author of the brand new book Story Mode: Video Games & the Interplay Between Consoles & Culture, which you can purchase here. If you are as tired as we are of thinking about what the Democrats are up to or whatever, you’ll enjoy this conversation about Fortnite Lore, our favorite games, the neverending quest for the media to link real world violence to video game violence, how Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty predicted modern America, and a whole lot more.

Welcome to Hell World

Luke O’Neil

A reminder that if you subscribe to Hell World for a year you’ll also get a six months paid subscription to Foreign Exchanges by Derek Davidson and Forever Wars by Spencer Ackerman (or vice versa).

“I think something is wrong with me but I also think it is the same thing that’s wrong with everyone so maybe it doesn’t matter,” goes this essay, which I am being told is “one of the good ones.”

The general consensus seems to be that we’re waiting for some ideal version of America to finally arrive and the thinking goes that the defeat of Trump the first bad president is supposed to have ushered us along on that path or at the very least forestalled the arrival of a much worse possible outcome but I don’t have much faith that any of that is true. I think that we are now in this cruel and unforgiving and merciless moment of unchecked violence and sickness and indifference to others the country we were always going to be and always have been no matter how many billions of prayers we’ve said to God or Thomas Jefferson or William Carlos Williams or John Prine or whoever. I think the ideal America is here now it’s a train we’ve been waiting to board that we’ve already been traveling on for miles we just didn’t realize it yet.

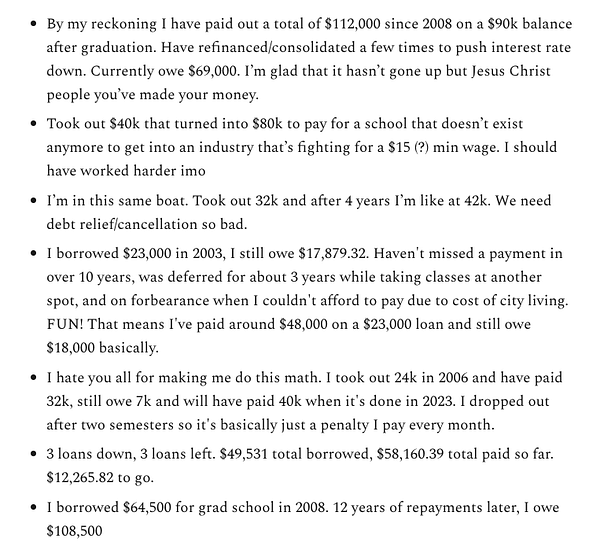

Also, with the idea of student loan forgiveness in the news again (not because it’s going to happen though lol) I thought it was worth looking back at some of the student loan-focused pieces in Hell World. This one is a good place to start including some testimonials from readers about how much they have ended up paying over the years.

The Flashpoint

Eoin Higgins

Work is hell—still.

I talked to workers from around the country about how they’re being mistreated and abused on the job.

Larry, a 37-year-old in the upper Midwest, told me that during his decade-long career in “a top quick service pizza corporation” he’s seen “insane abuse.” Companies train people to expect overwork and all manner of mistreatment.

Wages are so low that the only employees other general managers are high school kids, Larry said, and they don’t last.

“The money isn't enough to get you out of being economically precarious and they abuse you, so why even show up,” Larry said.

The business chews people up and spits them out. Larry told me he’s seen people “collapse on the job with back spasms, throw up, work bleeding.” He’s had to leave the career twice over health complications.

Also last week, a look at far-right comedian JP Sears’s recent transphobic comments.

Plus, I’m podcasting now with Callin. Check it out here:

Thanks for reading—sign up today to get these stories in your inbox.

The AP (Alex Pareene) Newsletter

Alex Pareene

I wrote about Tesla’s autonomous driving features, which you may have subsequently been introduced to through this viral Tweet of those features failing in ways that endanger the lives of people likely unaware that they are participating in a public beta test of Tesla’s autonomous driving features. I liken the arrival of these unsafe vehicles in our cities to the arrival of the automobile itself, which was not welcomed but instead resisted by people who recognized the car as a bringer of mass death. I suggest that if Elon Musk is aware of this history, he is likely also familiar with how, in spite of that resistance, the automobile came to win the battle for America’s city streets. (This is a good one to send to the Tesla enthusiast in your life.)

HEATED

Emily Atkin

If you like reading about how oil companies are continuing to screw the planet, my story from last week is for you.

Here’s the context: Last month, the Washington Post obtained a recording of a top Exxon lobbyist talking candidly about climate change. Speaking to a group of oil industry peers, Exxon’s vice president of advocacy Erik Oswald said the company considers climate change a risk—just not a “catastrophic, inevitable risk.”

The Post framed its story as Exxon “questioning the urgency” of climate change. But that’s putting things pretty damn lightly. Exxon is engaging in climate denial. It’s trying to convince the public things will be OK if we continue burning fossil fuels. This is objectively false.

To prove this, I teamed up with the good folks at Documented, a watchdog project investigating corporate power. Together, we dug up internal Exxon documents showing the company has considered climate risk “catastrophic” since the early 1980s. We also talked to several climate scientists who said catastrophic risks are indeed inevitable if humans don’t rapidly transition away from fossil fuels.

Our joint investigation comes amid heightened public scrutiny of Exxon for its misleading climate communication tactics, including a cadre of lawsuits and a Congressional investigation. I hope you’ll read it and share it widely—the planet (and I) will thank you.

BORDER/LINES

Gaby Del Valle & Felipe De La Hoz

It is a bit of an understatement at this stage to say that the Biden administration failed to adequately prepare for the evacuation of wartime allies and other refugees in the aftermath of its withdrawal from Afghanistan. Working under the impression that it would have much more time than it ultimately did, the government initially relied largely on the slow-moving Special Immigrant Visa process, followed by a special refugee designation for nonprofit workers and journalists, among others. When the Afghan government quickly fell and U.S. personnel including consular staff found themselves retreating to the Kabul airport, with no capacity to process refugee applications, the administration switched tracks and began using humanitarian parole to continue the evacuations.

Parole is a useful but flimsy designation intended to allow people otherwise without status to be let into the country for short periods and compelling humanitarian reasons. All in all, about 70,000 Afghans were paroled into the United States. However, many never made it to the airport in time to be flown out, and so U.S. officials began encouraging would-be refugees to file applications for parole from abroad (at a cost of $575 each). As we wrote in last week’s BORDER/LINES, waves of adjudications are starting to come back now, and signs point to the government’s plan to deny the vast majority of these applications.

Denial letters shared with journalists laid out almost impossible standards of evidence, including that applicants be personally at risk of persecution by the Taliban and that they be either in Afghanistan or at imminent risk of being returned there, despite the U.S. government’s encouragement that Afghans flee to third countries and send their applications from there. For those applicants who are denied, it’s the end of the road, as there’s no appeals process. They might still be able to get into the standard refugee process, but that’s a big if. As one attorney bemoaned, it was a “bait and switch” by U.S. officials.